Votre panier est vide

Besoin d'inspiration ?

Rendez-vous dans le programme en ligne du GrandPalais

Article -

L’homme de la Renaissance est très curieux. Il observe le monde pour en comprendre les lois

Renaissance man was very inquisitive. He observed the world in order to understand its laws

Renaissance man asked questions of himself, his soul, and also his body. Anatomists carried out dissections to study how the body works, though they were still rare and controlled by the religious authorities. The printing press allowed them to put together illustrated anatomy books and transfer their knowledge. The greatest anatomist of the Renaissance was Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), who was Flemish. This knowledge of the human body was essential for progress in medicine. Artists also wanted to perfect the representation of the body for the sake of realism.

The printing process was invented in China in the 11th century. Around 1440 Gutenberg, a goldsmith from Mainz, introduced the technique in Germany. He created movable type out of metal that the printer could re-use to typeset several books. So production then became more important. In the Middle Ages monks would re-copy books by hand. This was long, detailed work. As well as being produced faster, books cost less and were therefore accessible to more people. In this way printing contributed to the spread of knowledge. The first book, issued from his workshop in 1455, was a Bible.

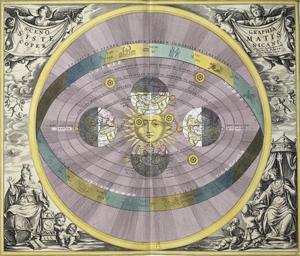

Born in Poland, Copernicus revolutionized astronomy. He was the first to understand that the Sun is at the centre of the universe and the Earth revolves around it. This view of the world went against the teachings of the Church which held back scientific progress. As far as it was concerned, man (and therefore the earth) was at the centre of the universe and the stars moved around it. “After lengthy studies I am now convinced that the Sun is a fixed star surrounded by planets which revolve around it, and for which it is the centre and burning torch…” Nicolaus Copernicus, On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, 1543.

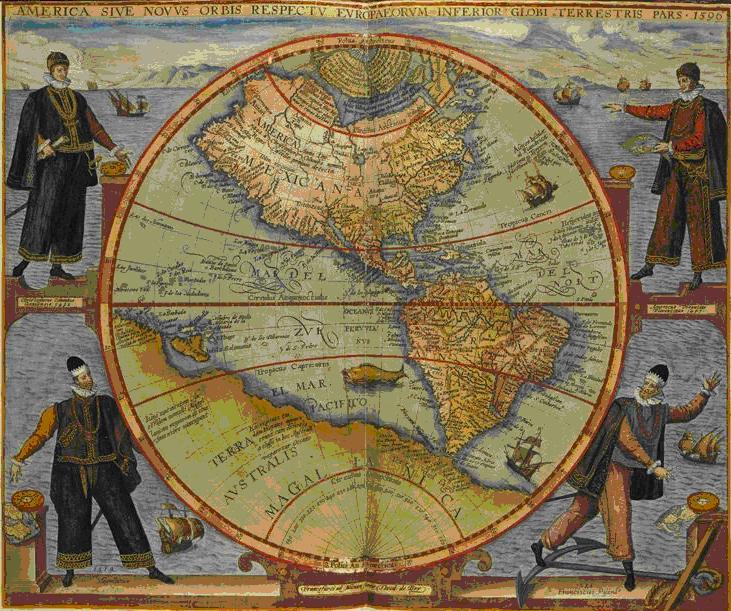

The great discoveries marking out the Renaissance were geographical. They were linked to the inventions which made the journeys possible. Seafarers in the Middle Ages stayed close to the shores as they did not have good maps and suitable boats. In the 13th century they had access to the compass, which had been invented by the Chinese in the 10th century. So Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, set out on a trip to China that lasted 20 years. He described his journey in the book known as The Travels of Marco Polo. During the Renaissance, Portuguese navigators developed ships that were suited to voyages of discovery: the carvel and carrack. They are easy to steer and make good progress even against a headwind. They explored the African coasts in search of slaves and gold for commercial trade. Thanks to the astronomical instrument called the astrolabe, navigators were able to guide themselves by the position of the sun and stars.

In 1475 the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama was the first European to reach India by sea, via the Cape of Good Hope on the southern headland of Africa.

In 1492 Christopher Columbus attempted to reached Asia by going West in the service of the Spanish crown. Without realizing it, he discovered the islands of Cuba and Haïti in Central America.

In 1519 Magellan left Spain with five sailing ships to explore the South American coasts. He discovered the strait that bears his name and made it through to the Pacific Ocean. He was killed in the Philippines, but his companion Del Cano came back with one ship, bringing proof that the earth is round.

Votre panier est vide

Besoin d'inspiration ?

Rendez-vous dans le programme en ligne du GrandPalais

See content : In the fantastic world of Eva Jospin: 8 questions for the artist

Article -

At the Grand Palais, Eva Jospin's "Grottesco" exhibition offers a timeless journey. Mysterious caves, sculpted nymphaea, petrified forests and "embroidered tableaux" come together to form a world apart. In this interview, the artist reveals her sources of inspiration, her relationship with cardboard and embroidery, and the way she turns each viewer into an explorer of her fantastical landscapes.

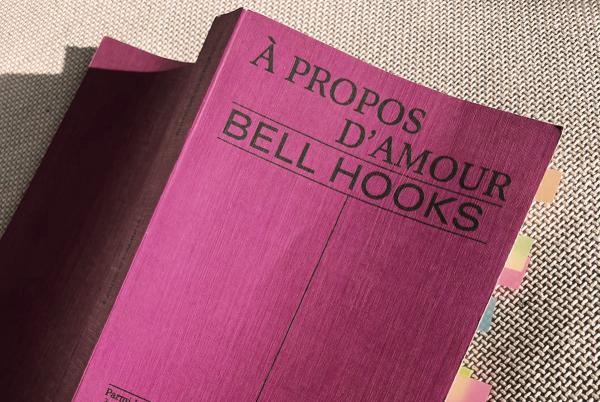

See content : Recommended reading: the foundational text of Mickalene Thomas’s exhibition All About Love

Article -

Mickalene Thomas's exhibition All About Love celebrates the intimacy, sensuality and power of Black women. It owes its title to bell hooks' book, All About Love: New Visions (1999), which presents love as a force for transformation and empowerment.

See content : Portraits of intimacy: the muses of Mickalene Thomas

Vue de l'exposition « Mickalene Thomas, All About Love », Les déesses noires, au Grand Palais, Paris

Article -

Mickalene Thomas celebrates Black women through intimate, sensual and powerful portraits. In large-scale works, her friends, lovers and icons become both muses and the protagonists of their own image.